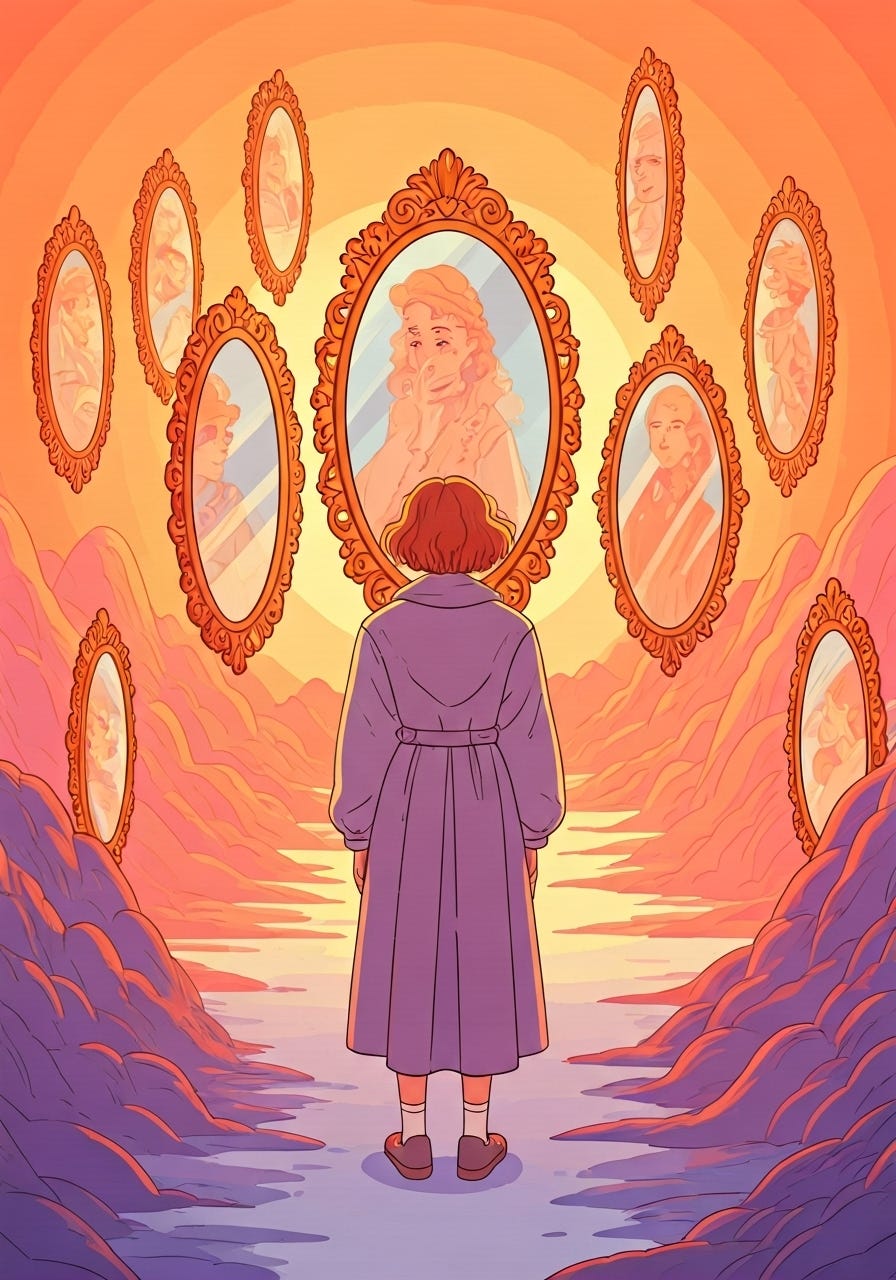

I stand before my bathroom mirror, peering into a face I’ve known for decades. It’s a familiar sight, youthful enough, with quirks I’ve come to accept, even cherish. I’m relatively happy with this reflection, this version of me. It’s the me I carry in my mind, the one I assume the world sees. But then I visit a photographer for a driver’s license renewal, and the image that emerges is jarring. The person in the photo is older, less vibrant, almost a stranger. The harsh lighting and unforgiving lens reveal someone I don’t recognise. It’s a moment of dissonance that forces a question: Who is the real me, the face I see in my private mirror or the one captured in this stark, official snapshot?

This experience isn’t just about a bad photo. It’s a metaphor for a deeper, more perplexing truth: the image we hold of ourselves is uniquely ours, often misaligned with how others perceive us. Our inner vision, shaped by memory, emotion, and selective focus, clashes with the external world’s view, which is filtered through its own biases, assumptions, and fleeting impressions. And beyond these two lies a third question: Who are we, really? Are we the person we believe ourselves to be, the one others see, or something else entirely? This tension between self-perception, external perception, and objective reality forms a kind of existential matrix, one where the “true” self is elusive, perhaps unknowable.

The Inner Mirror: The Self We Construct

The image we hold of ourselves is a carefully curated story. It’s built from years of experiences, aspirations, and the narratives we tell ourselves to make sense of who we are. In my mind, I might be the witty, compassionate, slightly quirky person I aspire to be. This inner self is forgiving, it glosses over my flaws, emphasises my strengths, and clings to a version of me that feels timeless. Psychologists call this the “self-concept,” a mental model that’s both a comfort and a shield. It’s why I can look in the mirror and see a face that feels “young” even as the years accumulate. My inner mirror is kind, but it’s also subjective, shaped by my desires and insecurities.

This self-concept isn’t static. It evolves with our experiences, but it’s also resistant to change. When I see that unflattering driver’s license photo, it challenges my internal narrative. I recoil because it doesn’t align with the me I’ve constructed. This dissonance isn’t just vanity, it’s a clash between my subjective reality and an external one. And yet, I cling to my inner image, because it’s the one that feels most authentic, most mine.

The External Lens: The Self Others See

But the world doesn’t see my inner mirror. Others form their impressions based on fragmented encounters, my words, actions, appearance, and even the context of a single moment. To the photographer, I’m a fleeting subject under harsh lights. To a colleague, I might be the person who spoke too quickly in a meeting. To a friend, I’m a reliable confidant, or perhaps, on a bad day, a distant one. These perceptions are shaped by their own biases, expectations, and fleeting glimpses of me. They see a version of me I might not recognise, just as I see versions of them they might not endorse.

This external perception can be jarring, like that driver’s license photo. It’s why we cringe when we hear our own voice on a recording or see ourselves in a candid video. The world’s lens is less forgiving than our own, and it often captures details we’d rather ignore. But is this external view any truer than our inner one? Others don’t have access to our thoughts, our intentions, or the context of our lives. Their perceptions are incomplete, colored by their own experiences and assumptions. If my inner mirror is subjective, the external lens is equally so, just in a different way.

The Elusive Truth: Which Self is Real?

This brings us to the heart of the matter: If my self-perception and others’ perceptions of me are both flawed, where does the “real” me reside? Am I the good soul I believe myself to be, striving to live up to my values? Or am I the flawed, perhaps less admirable person others sometimes see, a troglodyte in their eyes, an imposter in my own? Or is the truth somewhere else, in a space we can’t fully access?

Philosophers and psychologists have wrestled with this question for centuries. The existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre argued that we are defined by our actions, not our intentions, suggesting that the external world’s view holds weight. Meanwhile, Carl Rogers, a humanist psychologist, emphasised the importance of the “authentic self,” the person we feel we are when we align with our true values. Both perspectives hint at a paradox: our identity is both self-determined and shaped by others. We exist in a dynamic interplay between the internal and external, never fully reducible to either.

Perhaps the “real” self isn’t a fixed entity but a process—a constant negotiation between who we think we are, who others think we are, and the actions we take in the world. The driver’s license photo isn’t the whole truth, but neither is my private mirror. Both are snapshots, incomplete and context-bound. The real me might be the sum of these perspectives, plus something more: the choices I make, the values I uphold, the way I navigate the gap between my inner world and the outer one.

Living in the Matrix of Identity

So, which matrix is real? The answer, frustratingly and beautifully, is that there’s no single truth. We live in a complex web of perceptions, each offering a piece of the puzzle. The inner self provides meaning and continuity, the external self grounds us in social reality, and the “true” self, if it exists, emerges in the messy, ongoing dance between the two.

This realisation can be unsettling, but it’s also liberating. If no single perspective holds the whole truth, we’re free to shape our identity through our actions and intentions. We can strive to align our inner mirror with the external lens, not by conforming to others’ views but by living authentically in ways that resonate with both. The driver’s license photo might not capture my essence, but it reminds me that I’m seen by others, and that matters. The face I see in my private mirror might not be the whole story, but it’s a vital part of how I navigate the world.

In the end, the question isn’t “Which self is real?” but “How do I live with all these selves?” By embracing the tension, we can find a kind of truth, not a static image, but a dynamic, evolving one, reflected in the choices we make and the connections we forge. The mirror, the photograph, and the eyes of others all offer glimpses of who we are. The challenge, and the beauty, lies in weaving them into a life that feels true.