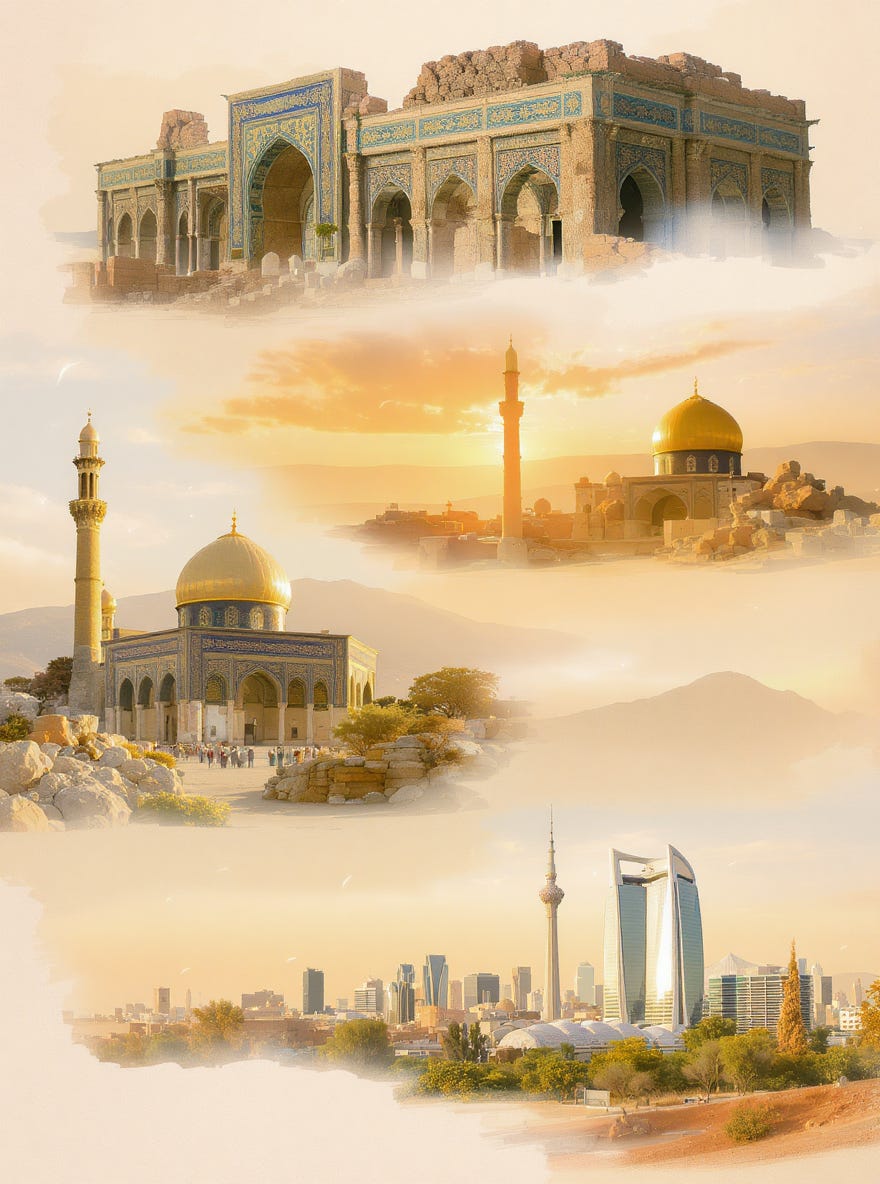

Ancient Times: The Cradle of Civilisation

Iran, historically known as Persia, boasts one of the world's oldest civilisations. From the Elamite kingdoms around 2700 BCE to the rise of the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BCE) under Cyrus the Great, ancient Persia was a beacon of culture, governance, and innovation. The Achaemenids established a vast empire stretching from Egypt to India, famed for their administrative prowess and respect for diverse cultures. Subsequent dynasties, including the Parthians and Sassanids, solidified Persia's role as a global power until the Arab conquest in the 7th century introduced Islam, reshaping its religious and cultural landscape.

The 20th Century: A Century of Transformation and Turmoil

The 20th century marked a period of profound change for Iran, shaped by modernisation, foreign influence, and internal strife.

Early 20th Century: The Qajar Decline and Constitutional Revolution

Under the Qajar dynasty (1789-1925), Iran faced economic stagnation and foreign domination by Britain and Russia. The Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911, driven by intellectuals, merchants, and clergy, sought to curb royal autocracy, resulting in a constitution and parliament. However, weak governance and foreign interference persisted, leaving Iran vulnerable.

The Pahlavi Era: Modernisation and Authoritarianism

In 1925, Reza Shah Pahlavi seized power, founding the Pahlavi dynasty. Inspired by Turkey's secular reforms, he pursued rapid modernisation, building infrastructure, secularising education, and unveiling women. His authoritarian rule, however, alienated the clergy and suppressed dissent. During World War II, Allied forces occupied Iran to secure oil and supply routes, forcing Reza Shah's abdication in 1941 in favour of his son, Mohammad Reza Shah.

The post-war period saw a surge in nationalism. In 1951, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh nationalised the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, challenging British dominance. His democratic aspirations alarmed Western powers, leading to a CIA-backed coup in 1953 that restored the Shah's authority. This event sowed deep resentment, fuelling anti-Western sentiment.

The Shah's "White Revolution" in the 1960s aimed to modernise agriculture, grant women suffrage, and reduce clerical influence. While it spurred economic growth, it widened inequality and alienated traditionalists, particularly the Shia clergy. Opposition grew, led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, exiled in 1964 for denouncing the Shah's reforms and US influence.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution

By the late 1970s, economic mismanagement, repression, and cultural disconnect fuelled widespread unrest. Protests by students, workers, and clerics culminated in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The Shah fled, and Khomeini returned to establish the Islamic Republic, a theocratic state blending clerical rule with limited democratic elements. The revolution promised justice and independence but soon descended into authoritarianism.

The new regime faced immediate challenges. The 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, initiated by Saddam Hussein, devastated Iran's economy and killed hundreds of thousands. Internally, the regime purged political opponents, including leftists and liberals, consolidating power under Khomeini's vision of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist).

Late 20th Century: Reform and Resistance

After Khomeini's death in 1989, Ali Khamenei became Supreme Leader, maintaining hardline control. The 1990s saw tentative reforms under President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), who advocated for civil society and dialogue with the West. However, conservative factions stifled his efforts, and the 2005 election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad marked a return to confrontational policies, particularly over Iran's nuclear programme, which invited international sanctions.

The Plague of Extremist Islam

Since 1979, Iran has grappled with the consequences of extremist interpretations of Islam under its theocratic regime. The Islamic Republic's ideology, rooted in Khomeini's vision, prioritises ideological purity over pluralism, enforcing strict social codes, gender segregation, and censorship. The morality police, tasked with upholding Islamic dress and behaviour, have become symbols of oppression, exemplified by the 2022 death of Mahsa Amini, which sparked nationwide protests under the slogan "Woman, Life, Freedom."

The regime's focus on exporting its revolutionary ideology, through proxies like Hezbollah and support for regional conflicts, has strained Iran's economy and isolated it globally. Sanctions, coupled with mismanagement, have fuelled inflation, unemployment, and poverty, eroding public support. While the regime maintains control through the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and propaganda, dissent simmers among a young, educated population yearning for freedom and opportunity.

Possible Outcomes After the Current Regime

The future of Iran post-regime remains uncertain, shaped by internal dynamics and global pressures. Several scenarios are plausible:

Democratic Transition: A peaceful collapse of the regime could lead to a secular, democratic government. Pro-democracy movements, galvanised by protests like those in 2022, may unite diverse groups, including students, workers, and ethnic minorities. However, factionalism and the IRGC's entrenched power pose challenges to a smooth transition. International support for institution-building could be crucial.

Reformed Theocracy: Moderate clerics and pragmatists within the regime might push for gradual reform to preserve the Islamic Republic while loosening social and political restrictions. This could mirror China's economic opening while retaining authoritarian control. However, hardliners' resistance and public distrust may limit this path's viability.

Fragmentation and Chaos: A power vacuum could trigger civil conflict, with ethnic groups like Kurds, Baluchis, and Azeris seeking autonomy. The IRGC or rival factions might vie for control, risking a Syria-like scenario. Foreign intervention, particularly by regional powers, could exacerbate instability.

Military Rule: The IRGC, wielding significant economic and military power, could establish a military dictatorship, replacing clerical rule with nationalist authoritarianism. This might stabilise Iran temporarily but would likely perpetuate repression and economic woes.

Iran's youth, comprising over 60% of the population under 30, will play a pivotal role. Their exposure to global ideas via the internet and their frustration with ideological rigidity signal a desire for change. The diaspora, with millions of Iranians abroad, could also contribute expertise and capital to a post-regime state.

Iran's history reflects a resilient nation navigating empires, revolutions, and ideological extremes. The 20th century's upheavals, culminating in the Islamic Republic, have left deep scars but also a legacy of resistance. As the current regime faces mounting pressure, Iran's future hinges on its people's ability to forge a path toward inclusivity and stability, reclaiming the nation's ancient promise as a crossroads of culture and progress.